Recent livestock disease investigations

Case 1: Melioidosis diagnosed in alpacas in the Perth metropolitan region

- Two cases of melioidosis have been confirmed in alpacas within the Perth metropolitan region.

- One case involved 2 deaths following clinical signs of reduced body condition and dyspnoea: multiple others were affected with mild respiratory signs. The clinical signs did not resolve with antibiotic treatment. The owner contacted a DPIRD field veterinarian, and a post-mortem was performed at DPIRD’s Diagnostic Laboratory Services (DDLS) in South Perth.

- Another case of melioidosis was diagnosed at a similar time, also within the Perth metropolitan region.

- Melioidosis was confirmed by laboratory testing in both cases via culture and PCR. As Melioidosis is resistant to a variety of antibiotics, antimicrobial susceptibility testing at DDLS can guide selection of an appropriate antimicrobial.

- Melioidosis results from infection by the bacterium Burkholderia pseudomallei, which is endemic in the tropical northern parts of Australia. It has also been diagnosed 10 times in Western Australia since 1966, mostly in the Kimberley region with several sporadic incidents in Gidgegannup, Chittering and Toodyay areas after very heavy rainfall or significant soil disturbances. The bacterium is found in soil and can survive for prolonged periods where there is optimal moisture, temperature and pH. During increased rainfall or soil disturbances such as earthworks, the bacterium can move onto the soil surface where it can infect animals and people. Camelids and goats are especially susceptible.

- Camelids may develop respiratory disease with coughing, nasal discharge and difficulty breathing. Other clinical signs may include hindleg weakness, ataxia, wasting and sudden death. For clinical signs in other animals including sheep, pigs, cattle, and horses, see the DPIRD melioidosis webpage.

- Melioidosis is a zoonotic disease. Most infections in people occur through exposure to the bacteria in soil or water. There have not been any clearly documented cases of zoonotic spread and the risk of interspecies spread is considered to be very low. While melioidosis is not a reportable disease of livestock in Western Australia, confirmed infection in people is a notifiable disease to the WA Department of Health. Veterinarians who have diagnosed melioidosis in animals should contact DPIRD for advice and report the diagnosis to the WA Department of Health. People who are concerned about their risk of melioidosis should consult their general medical practitioner, their local public health unit, or the WA Notifiable Disease Unit.

- For more information see the Melioidosis in animals webpage.

If you see signs of disease in animals that could be melioidosis, please contact Dr Anna Erickson, DPIRD Senior Field Veterinary Officer for assistance: 08 9881 0211, mobile 0437 801 416, email: anna.erickson@dpird.wa.gov.au.

Any questions relating to public health, including if you think staff or clients may have been exposed to a potential source of infection, should be referred to WA Health’s Metropolitan Communicable Disease Control service on 08 9222 8588 or 1300 MCDCWA (1300 623 292).

Case 2: Lumpy skin disease (LSD) excluded in abattoir

- Three animals with skin lesions were detected at ante-mortem by the on-plant veterinarian in a Kimberley region abattoir. Each animal displayed 6 to 7 external granulomatous nodules on the neck and around the shoulder of the animal. There were no other clinical signs.

- The location of these granulomatous nodules cranial to the right shoulder in these animals were potentially consistent with an injection site reaction. Fixed and fresh samples of the lesions were sent to DDLS and ACDP laboratories for LSD rule out.

- Capripox virus real time PCR (Bowden et al. 2008) returned a negative result for LSD.

- It is important to check for LSD in cattle that have clinically consistent signs. Clinical signs of LSD in cattle include ocular and nasal discharge, decreased milk production in lactating cattle, inappetence and pyrexia lasting 6 to 72 hours. Within 48 hours of onset of fever, firm skin nodules of 2 to 5 cm diameter will erupt, particularly on the head, neck, limbs, udder, genitalia, and perineum. Skin lesions are full skin thickness. The subscapular lymph node is generally enlarged. Cattle may lose body condition rapidly.

- Transmission of the virus is through biting insects, including flies, mosquitoes, midges and ticks. It can also be spread by the movement of infected animals or contaminated products and equipment. The virus is highly contagious affecting cattle and water buffalo. The virus cannot be spread to humans or to other species, such as sheep or goats.

- See below for the sampling guide for excluding LSD.

- To prove WA is free of significant diseases affecting trade and to boost early detection of such diseases, the Significant Disease Investigation program provides a subsidy of $330 to private veterinarians for an initial field and laboratory investigation of significant disease incidents in livestock. Contact your DPIRD veterinarian for more information and approval.

- The Northern Australian Biosecurity Surveillance (NABS) network provides cost subsidies to support veterinarians conducting significant disease investigations (SDI) of production animals in isolated areas of Northern Australia. The outcomes of NABS SDI’s contribute to our understanding of the endemic diseases affecting producers in Northern Australia. For more information and to register with the NABS network, please visit the NABS website, contact a NABS veterinarian or contact your closest DPIRD veterinarian.

- Lumpy skin disease is a reportable disease in Australia. Eradication of LSD is difficult and early detection is essential for successful control and eradication. If you investigate a case with these signs, contact your DPIRD veterinarian or the Emergency Animal Disease Hotline on 1800 675 888.

- Private veterinarians can obtain Lumpy skin disease replacement sampling kits from DPIRD. Contact your DPIRD veterinarian for more information.

More information on LSD

- DPIRD webpage: Lumpy skin disease prevention and preparedness

- Animal Health Australia, LSD information and producer biosecurity plans

- Emergency Animal Disease Bulletin no. 121

Lumpy skin disease sampling guide

| Sample | Quantity | Specimen storage |

|---|---|---|

| 10 mL whole blood EDTA (purple top) | One per affected animal | Stand tubes upright in an esky containing ice packs. Do not allow direct contact with ice packs. |

| Fresh tissue biopsy from edge of the lesion in sterile specimen container | 2 per animal | Chilled/refrigerated |

| Fixed tissue biopsy from the edge of the lesion in formalin | 2 per animal | Room temperature |

| Photos of lesions | As many as possible | Email with submission form to ddls@dpird.wa.gov.au |

Case 3: Neurological signs in an ewe, confirmed as Listeriosis

- A producer in the south-west contacted a DPIRD field veterinary officer after observing neurological signs followed by death in 2 sheep. A third sheep developed clinical signs. These sheep were of mixed ages and were in confined areas on silage and hay. Treatment was trialled in the previous two animals including subcutaneous magnesium and calcium solution, oral glucose, antibiotics and NSAIDs. No response to treatment was noted in either animal.

- On clinical examination the sheep was in lateral recumbency, actively paddling with torticollis and chewing motions, facial twitching, ataxia when standing and full body tremors. The menace response of this sheep was intact and vital signs were within the expected range.

- There were no notable lesions on post-mortem. A base sample set of fixed and fresh tissue was collected as well as antemortem blood samples, urine, feed samples and brain swabs. As this sheep fitted the transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE) surveillance program eligibility criteria, TSE samples were also collected to rule out scrapie, an exotic disease that would affect access to international markets. TSE samples in sheep include 2 to 3 cm fresh spinal cord, fresh dorsal cerebellum and the rest of the brain and brainstem fixed whole.

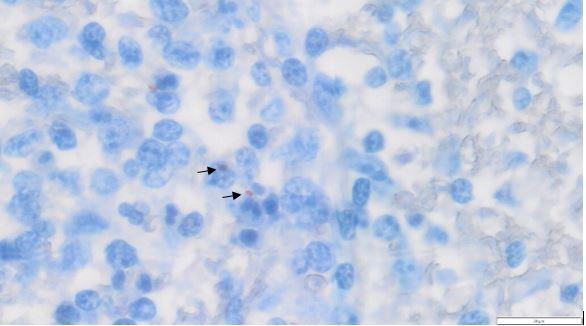

- Laboratory testing at DPIRD Diagnostics and Laboratory Services (DDLS) identified Listeria sp. from the brain swab in combination with distinctive lesions in the spinal cord and brain on histopathology.

- TSE testing returned a negative result, assisting in supporting Australia’s ‘free of BSE and scrapie’ classification to maintain access to international markets. Testing for lead toxicosis was also negative.

Investigations of neurological disease in sheep and cattle may be eligible for subsidies under the National Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathy (TSE) surveillance program. For questions and further information on the TSE program, talk to your DPIRD Field Veterinary Officer or WA’s TSE surveillance program manager Dr Will Janson on 08 9780 6233.

In spring, be on the lookout for

| Disease and clinical signs | Samples (additional to base set) |

|---|---|

Worms in sheep and cattle

Read more on sheep worm control. Read more on beef cattle worm control. | Ante-mortem:

Post-mortem:

|

Polioencephalomalacia (PEM) in sheep and cattle

Read more on DPIRD’s PEM webpage. | Ante-mortem:

Post-mortem:

If neurological signs are present in sheep 18 mths to 5 yrs and cattle 30 mths to 9 yrs, discuss subsidies for TSE testing with your DPIRD veterinarian.

|

Listeriosis

| Ante-mortem:

Post-mortem:

If neurological signs are present in sheep 18 mths to 5yrs and cattle 30 mths to 9 yrs, discuss subsidies for TSE testing with your DPIRD veterinarian.

|

Also include base samples and any clinical or gross lesions in submissions. For advice on sample submission, contact your DPIRD field veterinary officer, the sampling and post-mortem resources webpage or phone the duty pathologist on 08 9368 3351.

If you see nervous/neurological signs in your livestock, phone a veterinarian. Some exotic diseases, such as transmissible spongiform encephalopathy, can cause similar signs. Testing helps to prove that WA is free from such diseases and further supports the industry.

Membership exams done and dusted!

A huge congratulations to all veterinarians that completed their membership examinations in 2023. There were a number of DPIRD vets that passed their membership examinations in various disciplines. Congratulations on this massive accomplishment.

- Dr Kristine Rayner, Medicine of Sheep

- Dr Caitlin Hargan, Veterinary Epidemiology

- Dr Emily Ainsworth, Veterinary Epidemiology

Virulent footrot sample collection

Virulent footrot is caused by the bacterium Dichelobacter nodosus and starts as interdigital inflammation, usually on more than one foot. Lesions will have moisture, reddening and hair loss to varying degrees. Lesions are often accompanied by necrotic tissue and a distinct odour. As the disease progresses, under-running of the hoof, generally starting at the heel, is noticed. Lameness may or may not be present.

To diagnose virulent footrot, samples must be taken. A swab is collected from the foot lesion and placed into suitable transport medium provided by DPIRD. Samples are then clearly labelled, packaged and sent to DPIRD’s Diagnostic Laboratory Services (DDLS) where a qPCR test is performed. A DDLS requisition sheet must accompany all samples; this can be obtained from the DPIRD website. To preserve the integrity of the samples, it is preferred that they are sent with an ice block. Samples collected on a Friday should be cold stored until Monday and then posted.

Contact your local DPIRD office if you require a sample medium for virulent footrot lesions.

Courier samples to:

DDLS Animal Pathology

Duty Pathologist Specimen C Block

DPIRD 3 Baron Hay Court

South Perth WA 6151

See the DPIRD webpages for information on benign and virulent footrot in WA.

For questions and further information on virulent footrot, talk to your DPIRD field veterinary officer or WA’s virulent footrot program manager Dr Sarah Float on 08 9780 6126.

Update to DDLS Fees and Charges for the new financial year

The Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development Diagnostics and Laboratory Services (DDLS) - Animal Pathology, Western Australia (formerly DAFWA Animal Health Laboratories) provides a variety of services including testing for disease surveillance and control, testing to support export certification, development of new tests, research on livestock diseases and laboratory support for research on animal production.

The updated services, products and fees manual describes the full range of tests offered, information on sample collection, fees for service and service fee exemptions. To discuss our range of services, call 08 9368 3351. Our office hours are 8:30 am to 4:30 pm Monday to Friday.

See the DPIRD (agriculture and food) services, products and fees 2023-2024 manual to view the updated services and fees.

Livestock disease investigations protect our markets

Australia’s ability to sell livestock and livestock products depends on evidence from our surveillance systems to prove we are free of livestock diseases that are reportable or affect trade. The WA Livestock Disease Outlook – for vets summarises recent significant disease investigations by Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (DPIRD) veterinarians and private veterinarians that contribute to that surveillance effort. Data from these investigations provides evidence that WA is free from these diseases and supports our continuing high health status and access to high valued markets.

Find out more about WA's animal health surveillance programs.

Feedback

We welcome feedback. To provide comments or to subscribe to the veterinary edition of the monthly newsletter, WA Livestock Disease Outlook, email: waldo@dpird.wa.gov.au. To see previous issues of the WALDO – for vets newsletter, please visit our archive page. Producer versions of this newsletter are available on the WA Livestock Disease Outlook archive page.