Introduction

The cane toad (Rhinella marina) or giant toad is native to south and central America. It has been introduced to many countries, including northern and eastern Australia. The cane toad is a declared pest under the Biosecurity and Agriculture Management Act 2007 (BAM Act) in Western Australia (WA).

The Western Australian Organism List (WAOL) contains information on the area(s) in which this pest is declared and the control and keeping categories to which it has been assigned in WA. Use the links on this page to reach cane toad in WAOL.

Identification and behaviour

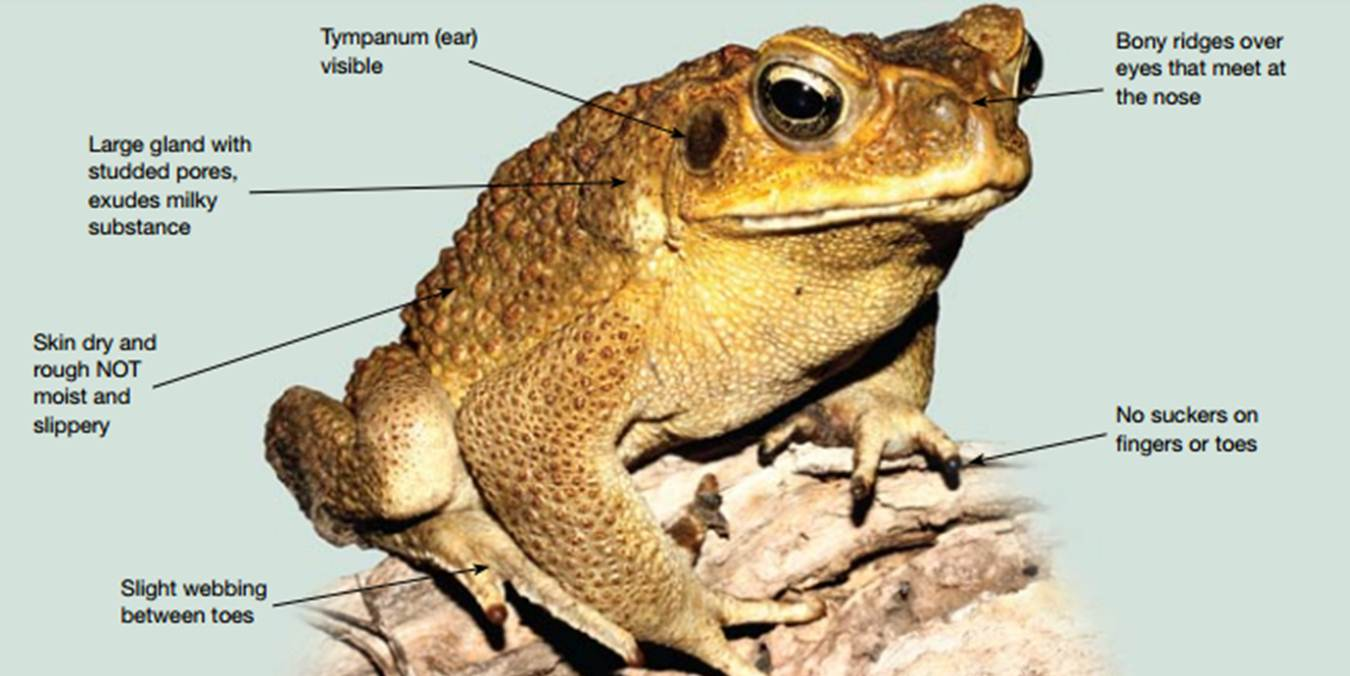

Cane toads are the only true toads present in Australia. They are heavily-built and are typically 100–150mm in length. They can grow to more than 230mm and over 1kg in weight, but in areas with high toad densities individuals rarely exceed 100mm in length. The skin of cane toads is dry and rough rather than moist and slippery like many native frogs.

The backs of male toads have large warty lumps that feel like sandpaper when rubbed, while females have slightly smoother skin with less prominent lumps. The body colour on top ranges from dull brown to yellowish or blackish (never bright greens, yellows or reds) and there is rarely any marked pattern. The light underparts are usually mottled with brown.

The large glands behind the head can sometimes exude a poisonous milky substance when the toads are disturbed. Other distinctive features include a visible eardrum, bony ridges on the head, slight webbing between the toes (but not the fingers) and lack of enlarged pads (suckers) on the digits.

The call of the male is a guttural trill, sustained for about 30 seconds, and very different from most native frog calls.

Cane toads are most active at night, often in open areas such as roads and lawns. They sometimes congregate beneath streetlights and other lights to catch insects. On land, toads walk and hop short distances, but do not leap or climb smooth surfaces like some native frogs. They also typically sit more upright than many native frogs. Where toads have established in the wild they can occur in much larger numbers than native frogs.

The egg masses (spawn) of cane toads are unlike those of most native frogs and the tadpoles are also different. Toads produce chains of black eggs about 1mm in diameter enclosed in a thick transparent gelatinous cover, forming long strands about 3mm thick.

Toad tadpoles are jet black and reach a maximum of about 30mm from head to tail. They have non-transparent abdominal skin, their bodies are wider than they are long and their tails are relatively short with a dark central muscle and clear fins. The tadpoles of native frogs are generally very dark (but not jet black) with lighter or transparent abdominal skin and longer tails. Toad tadpoles form large slow-moving groups at the water’s edge and do not rise often to the surface to ‘breathe’. In contrast, tadpoles of native frogs regularly rise to the surface, having developed lungs sooner.

Newly-formed toads (metamorphs) are small (9-11mm) compared to adults and are conspicuous by their large numbers and daytime activity near their watery breeding sites. They develop into juveniles that have a distinct camouflage pattern that diminishes with age.

Further information

For further information, or to report a cane toad sighting, please contact the Cane Toad Hotline 1800 44 WILD (1800 449 453), or the Department of Parks and Wildlife.