Recent livestock disease investigations

Liver fluke excluded in condemned sheep liver at Great Southern abattoir

- An on-plant veterinarian noted presumed parasitic tracts in a single liver at slaughter.

- One liver was condemned from a line of 300 8-month-old lambs.

- The on-plant veterinarian contacted the DPIRD Diagnostics and Laboratory Services (DDLS) on duty pathologist. Lab-fee exempt testing was granted to rule out Liver fluke (Fasciola hepatica), which is a reportable disease in Western Australia with interstate control measures in place to prevent entry into the state.

- The on-plant veterinarian submitted both fixed and fresh liver samples from the condemned liver as well as photographs.

- Laboratory testing excluded fascioliasis (Liver fluke) through absence of typical histopathology and fluke pigment.

- The agent causing the liver lesions was identified as Taenia hydatigena larvae undertaking hepatic migration prior to localisation in the peritoneum, where they are then identified as Cysticercus tenuicollis cysts. Cysts containing viable larvae were not detected. Extensive fibrosing and calcifying reaction suggests death of the larvae during the migration phase.

- Cysticercus tenuicollis cysts are commonly referred to as bladder worm. It is caused by the ingestion of eggs from the dog tapeworm Taenia hydatigena. It has little effect on sheep health or production and is of no concern for human health, however it causes economic losses due to condemnation of livers and trimming of cysts in the abdominal cavity of carcases at the abattoir.

- Pet and working dogs should be de-wormed monthly with a tapeworm treatment, and dogs should be prevented from accessing sheep carcases. Wild dogs and foxes can also carry the tapeworm that causes bladder worm in sheep.

- Sheep measles (Taenia ovis) is another tapeworm parasite which can cause significant economic loss due to rejection or trimming of sheep carcases. The parasite is carried by dogs, however the larval stage in sheep muscle results in an unsightly cyst which is not acceptable for human consumption, although it poses no concern for human health. Control involves preventing transmission of the tapeworm from dogs to sheep. Read more about sheep measles.

Read more in the Animal Health Australia bladder worm factsheet.

See the DPIRD webpages for more information on Liver fluke and Liver fluke testing and laboratory requirements for Western Australia.

Sudden death in hoggets in the Great Southern region

- A private veterinarian was called to investigate the sudden death of 50 one-year-old hoggets from a mob of 2,500 in the Great Southern region.

- The large mob was being run across several paddocks with access to replanted salt bush and appeared healthy with no obvious tail. The mob was unvaccinated with a low faecal egg count one month ago. The property has a history of York Road poison (Gastrolobium calycinum), a fluoroacetate containing plant.

- The private veterinarian had obtained approval from a DPIRD field veterinary officer for a SDI prior to the property visit. To prove WA is free of significant diseases affecting trade and to boost early detection of such diseases, the Significant Disease Investigation (SDI) program provides a subsidy of $330 to private veterinarians as well as an exemption on laboratory diagnostic fees for an initial field and laboratory investigation of significant disease incidents in livestock. Contact your DPIRD veterinarian for more information or approvals.

- A post-mortem was conducted on 2 animals with no significant findings indicating the cause of death. Base samples from each animal as well as blood samples from one healthy animal were submitted to DPIRD Diagnostic Laboratory Services (DDLS).

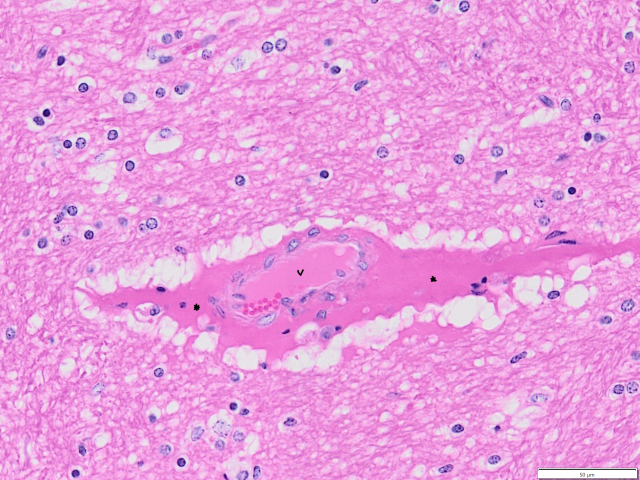

- Laboratory testing identified Clostridial enterotoxaemia (previously termed pulpy kidney) by detection of toxin in the ileal content and pathognomonic perivascular serum oedema within the brain on histopathology.

- Clostridial enterotoxaemia is caused by proliferation and toxin production of the bacterium Clostridium perfringens type D. This bacterium is a normal inhabitant of the intestines. Issues usually occur following a sudden change to low-fibre, high-carbohydrate diets such as sheep being moved onto lush, rapidly growing pasture, cereal crops or being fed grain. Clostridial enterotoxaemia most commonly occurs in rapidly growing unweaned or weaned lambs but can occur in older sheep following movement from poor to good quality feed. The disease is preventable by vaccination.

- Post-mortem signs commonly seen with enterotoxaemia in recently deceased sheep include haemorrhages under the skin and on the heart and kidney, straw-coloured or blood-tinged fluid with fibrin strands in the pericardial sac, friable small intestines containing a small volume of creamy fluid, rapid autolysis of the carcass within a few hours of death and, sometimes, rapid autolysis of the kidneys to become dark coloured and ‘jelly-like’, hence the colloquial name ‘pulpy kidney’.

See DPIRD’s webpage on pulpy kidney (enterotoxaemia) of sheep for more information.

ARGT confirmed cause of deaths and neurological signs in adult ewes

- A property in the Great Southern region experienced sudden death in 24 adult ewes of varying ages over 3 days duration. The sheep expressed clinical signs of staggering, full body tremors and recumbency and repeatedly falling over when attempting to move away from pressure. The ewes were not pregnant and had been moved into this paddock 3 weeks prior. Treatment with subcutaneous magnesium and calcium solution and electrolyte drench was trialled with no improvement.

- The producer contacted a DPIRD field veterinary officer for investigation. A property visit was organised for later that day.

- One liver was diffusely enlarged with rounded lobes on post-mortem without other significant findings. Blood samples were collected from affected and mildly affected animals as well as pasture samples.

- Laboratory testing at DPIRD Diagnostics and Laboratory Services (DDLS) identified annual ryegrass toxicity (ARGT) toxins in the rumen content and faecal samples as well as a ‘high-risk’ result on quantitative ARGT ELISA of the pasture sample. No lesions were seen in the brain to definitively confirm the diagnosis, but this is not uncommon in cases of ARGT.

- Lead toxicosis, a risk to human food safety and access to export markets, was excluded by kidney lead analysis.

- Cape tulip was also detected in the pasture sample, which is a toxic plant containing cardiac glycosides that can cause clinical signs similar to ARGT. Histopathological evidence of cardiac myonecrosis, lesions indicative of cardiac glycoside toxicosis, was not seen in this case.

- Annual ryegrass toxicity (ARGT) is an often fatal poisoning of livestock that consume annual ryegrass infected by the bacterium Rathayibacter toxicus (formerly known as Clavibacter toxicus). The bacterium is carried into the ryegrass by a nematode, Anguina funesta, and produces toxins within seed galls. Toxicity develops at seedset. Infected ryegrass seed remains toxic. Hay made from toxic ryegrass will also be toxic. All grazing animals are susceptible, including horses and pigs.

- Other diseases that may resemble ARGT include thiamine deficiency, pregnancy toxaemia, grass tetany, enterotoxaemia (pulpy kidney), and reportable diseases such as scrapie in sheep and bovine spongiform encephalopathy in cattle.

For more information, see the following DPIRD webpages:

- Annual ryegrass toxicity in livestock

- Testing hay for annual ryegrass toxicity (ARGT) risk

- Controlling annual ryegrass toxicity (ARGT) through management of ryegrass pasture.

Investigations of neurological disease in sheep and cattle may be eligible for subsidies under the National Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathy (TSE) surveillance program. For questions and further information on the TSE program, talk to your DPIRD field veterinary officer or WA’s TSE surveillance program manager Dr Will Janson at 08 9780 6233.

If neurological signs are seen in horses an SDI may be approved by your DPIRD veterinarian to test for the reportable disease Japanese encephalitis (JE). Suitable samples include; paired serum two weeks apart (10 mL), EDTA blood (5 mL) and CSF (2 mL in a plain blood tube (no clotting agents). After Hendra virus has been excluded, fresh and fixed brain samples are desirable.

Recent cattle deaths a reminder to prevent livestock access to sources of lead

- Recent deaths in cattle have occurred in the south-west as a result of lead ingestion.

- These cases are a reminder to consider lead toxicosis as a potential diagnosis in livestock displaying neurological signs. Animals affected by lead poisoning may become blind, unresponsive to their surroundings and bump into obstacles.

- Stock owners are reminded to remove or fence off items containing lead from grazing paddocks. Batteries, sump oil, paint, old machinery are all sources of lead and present a risk of both poisoning and residues.

- Preventing residues in meat and meat products is critical for human food safety and WA’s ongoing access to valuable export markets.

- For more information on preventing lead poisoning and residues in livestock visit the preventing residues in livestock webpage.

Lead poisoning in livestock sampling guide

| Ante-mortem samples | Post-mortem samples | Storage/ Transport |

|

Source samples:

| Blood samples: Mix with anticoagulant and chill; do not freeze.

Fresh samples: Chill/ refrigerate; do not freeze.

Fixed tissues: Keep at room temperature. |

In summer, be on the lookout for:

| Disease, typical history and clinical signs | Samples (additional to base set) |

|---|---|

| Nutritional myopathy in weaner sheep

Read more on vitamin E deficiency in sheep. | Ante-mortem:

Post-mortem:

Commercial feed:

|

| Annual ryegrass toxicity (ARGT)

Read more on annual ryegrass toxicity in livestock. Read more on management of ryegrass pasture. | Ante-mortem:

Post-mortem:

Pasture or fodder samples:

If neurological signs are present in sheep 18 mths to 5 yrs and cattle 30 mths to 9 yrs, discuss subsidies for TSE testing with your DPIRD veterinarian. If neurological signs are present in horses an SDI may be approved by your DPIRD veterinarian. Suitable samples to collect include paired serum 2 weeks apart, EDTA blood and after Hendra virus has been excluded CSF and fresh and fixed brain if available. |

| Water quality issues

Read more on water quality for livestock. | Ante-mortem:

Post-mortem:

Water samples:

See DPIRD’s webpage on the Sampling procedure for toxic algae. |

Also include base samples and any clinical or gross lesions in submissions. For advice on sample submission, contact your DPIRD field veterinary officer, the sampling and post-mortem resources webpage or phone the duty pathologist on 08 9368 3351.

See DPIRD’s webpages for the livestock disease veterinary sampling guide and veterinary sample packaging guide.

Refresh your knowledge of the National Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies Surveillance Program (NTSESP)

The National TSE Surveillance Program (NTSESP) conducts surveillance for bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE or mad cow disease) in cattle and scrapie in sheep. Typical BSE and scrapie do not occur in Australia, but Australia is required to have a surveillance program to provide assurance that BSE and scrapie is not present in the population.

Animal Health Australia (AHA) manages the NTSESP, and the project is planned and implemented through the TSE Freedom Assurance Program National Advisory Committee, comprised of representatives from relevant livestock industries, the Australian Government and state and territory animal health agencies. The OIE (WOAH) requires a certain number of testing points, within a 7 year period, based on the size of the living population. This is to ensure adequate surveillance for the disease and is used to provide Australia with its 'green' disease free status. In the past, Australia’s target, to achieve this status, was estimated at a minimum of 150,000 surveillance points during a 7 year moving window. This number is subject to change.

The NTSESP supports Australian trade by:

- maintaining a surveillance system for TSEs that is consistent with the OIE Terrestrial Animal Health Code

- assuring all countries that import our cattle and sheep commodities that Australia remains free of these diseases.

Eligibility criteria

- Species – only cattle and sheep are eligible for payment.

- Live examination – the animal should be examined while alive by the submitting veterinarian to independently establish the clinical state prior to euthanasia and sampling. Where this is not possible, video footage of the animal displaying clinical signs may be acceptable if the veterinarian has agreed to it.

- Age:

- Cattle: aged between 30 months and 9 years of age.

- Sheep: aged between 18 months and 5 years of age.

- Clinically consistent animal – at least 2 clinical signs consistent with BSE or scrapie (see below).

- Sample type and quality – submitters must submit complete samples of the correct tissues (brain and spinal cord) of diagnostic quality for TSE evaluation.

- Completion of required forms – each submission must include a completed laboratory submission form.

- Cannot claim rebates for more than 2 animals per disease incident per property.

Conflict of interest – the submitting veterinarian must not have an actual or perceived conflict of interest with the recipient of a payment arising from the NTSESP (e.g. a financial or family link to them), or must satisfy the relevant state agency that a clinically consistent animal could not have been reasonably submitted by an alternative veterinarian or biosecurity officer without an actual or perceived conflict of interest.

| Mental status | Sensation | Posture and movement |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Mental status | Sensation | Posture and movement |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

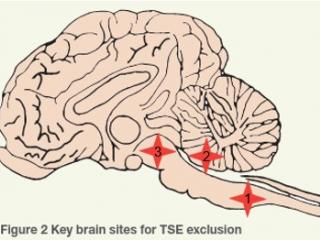

Where are the TSE testing sites?

There are 3 standard sites for histological exclusion of TSE:

- TSE site 1 = obex of medulla oblongata

- TSE site 2 = caudal cerebellar peduncles

- TSE site 3 = midbrain

Fixed brain tissue is used for histopathology and immunohistochemistry, which are the frontline tests to exclude TSEs. Unfixed cervical spinal cord (plus cerebellum for sheep) is collected in the event testing of the fixed brain tissue cannot exclude TSEs, and may be used for electron microscopy, immunoblot and mouse bioassay, as well as to further characterise a TSE if detected. In particular, the cerebellum of sheep is collected to facilitate further differentiation of classical scrapie and atypical/Nor98 scrapie by western blotting if required. Atypical scrapie is a non-contagious, sporadic, degenerative brain disease of older animals with no infection risk to other animals or humans.

Sampling

For the diagnostic exclusion of TSE, the entire intact brain and a segment of cervical spinal cord is required (see below). In addition, a base sample set of fixed and fresh samples (including blood samples) are needed to provide an alternative diagnosis.

Brain tissue should be removed as soon as possible after death, with the brainstem attached and intact. Fresh tissue should be collected and refrigerated (4ºC) without fixation as soon as possible.

Cattle:

- Fresh: 2 to 3 cm length of cervical spinal cord and/or medulla caudal to obex.

- Fixed: entire brain with residual cerebellum and brainstem attached. Submerged in 10% buffered formalin after removal.

Sheep:

- Fresh: 2 to 3 cm length of cervical spinal cord and/or medulla caudal to obex.

- Fresh: the dorsal (top) third of the cerebellum sampled via a coronal/ horizontal approach. Note: superficial sampling only to avoid compromising TSE Standard Site 2.

- Fixed: entire remainder of the brain with residual cerebellum and brainstem attached. Submerged in 10% buffered formalin after removal

Sampling key points

- Take care not to damage key TSE brain sites when removing the brain and taking fresh samples.

- Do not split the brain in half lengthways (longitudinally)

- Use enough 10% buffered formalin and a sufficiently large histology pot so the brain does not fix in a distorted position:

- Sheep: 1 L pot filled to the top with formalin

- Cattle: 2 L pot filled to the top with formalin.

- Allow the brain to fix at room temperature

- Check the case meets the TSE eligibility criteria – listed on the TSE lab submission form.

For information on brain removal, see the AHA NTSESP Field Guidelines (pages 23 to 25) or DPIRD’s brain removal techniques and TSE sampling benchaid.

Submission forms and rebates

Submission forms must be filled out to completion to be granted approval for TSE testing and rebates. This includes the producer claim form.

More information and TSE training

Animal Health Australia (AHA) has developed a training video to assist veterinarians and animal health specialists with the collection of brain tissue for testing of TSE. Watch the TSE sample collection training video on Youtube.

AHA has established a NTSESP training guide containing information for veterinarians and animal health officers who collect submissions for the National TSE Surveillance Program. See the NTSESP Training Guide webpage for more information.

For more information, see the DPIRD NTSESP webpage, the AHA NTSESP Field Guidelines 2022-2023 or contact the NTSESP WA State Coordinator Dr Will Janson on 08 9780 6233, 0408 672 946 or Will.Janson@dpird.wa.gov.au.

WA Emergency Animal Disease Veterinary Reserve training kicks off!

The Western Australian Emergency Animal Disease (EAD) Veterinary Reserve project is designed to increase the number of trained non-government veterinarians available to effectively contribute to an EAD response in Western Australia.

The first group of 23 veterinary reserve trainees began the program on 1 November 2023. The participation of non-government veterinarians and rapid response are two crucial elements in a departmental led response to an emergency animal disease outbreak. The training program will heighten the department’s capability to respond to an EAD by further developing the trainees' knowledge of the operational aspects of all phases of an EAD response.

Members of the Veterinary Reserve are required to make a commitment to the training program, and most importantly, if called upon, participate in the response to an EAD outbreak.

The training program includes a structured 2-day face to face workshop and a series of online TEAMS meetings that will involve a moderator led discussion of various aspects of an EAD response which will include, but not limited to, topics such as the current Australian biosecurity climate, legislation, area control principles and premises classification and control centre operations functions. TEAMS meetings are scheduled every second month. In addition, there is self-paced online course content.

Reserve members will be paid to complete the 45-hour training course over a 12 month period and then remain as a reserve member for 2 years after completing the course.

For further information, please contact Dr Simon Hollamby, DPIRD Veterinary Policy Officer at Simon.Hollamby@dpird.wa.gov.au.

Thank you for your ongoing work to protect WA’s biosecurity!

Thank you for continuing to work with DPIRD to protect Western Australia’s biosecurity and markets during 2023 and your ongoing support in 2024. Your awareness of reportable diseases and submissions to DPIRD Diagnostics and Laboratory Services (DDLS) are crucial to maintaining our excellent animal health status and protecting our markets.

Livestock disease investigations protect our markets

Australia’s ability to sell livestock and livestock products depends on evidence from our livestock disease surveillance and investigations to provide evidence Australia is free from many significant livestock diseases that affect trade.

Find out more about WA's animal health surveillance programs.

Feedback

We welcome feedback. To provide comments or to subscribe to the newsletter, email waldo@dpird.wa.gov.au. To see previous issues of the WALDO – for vets, please visit our archive page. Producer versions of this newsletter are available on the WALDO - for producers archive page.<