Distribution of slugs and snails

Slugs are pests of crops especially emerging canola, in the higher rainfall regions of WA. Slugs tend to be restricted to soils with a clay content.

Snails are found on all soil types. White Italian and vineyard snails prefer alkaline sandy soils; the small pointed snail is able to survive on all soil types even acidic soils. Liming areas where there are snails will aid snail survival.

The small pointed snails however, are only known to cause economic crop damage in high rainfall areas. Where as the vineyard and white Italian snails are known to cause crop damage in the Greenough flats (which is the region between Dongara and Geraldton) and the Geraldton region.

Identification and habits of pest slugs and snails

Slugs

Black keeled slug (Milax gagates)

Description

Black keeled slugs are 40-60mm long, black to brown with a ridge down their back.

Habits

This species burrows to a depth of 20cm or more surviving the heat of summer under the ground. Black keeled slugs re-emerge anytime conditions improve, such as after reasonable rainfall and when soil temperature decreases.

Reticulated slug (Deroceras reticulatum)

Description

Reticulated slugs are up to 50mm long, have dark brown mottling and range from light grey to fawn. There are usually two generations per year, in autumn and spring, however, this species can breed anytime under favourable conditions.

Habits

Reticulated slugs are found mainly at night on the soil surface. In summer, they usually shelter under rocks or logs, but also can move into loose or cracked soil.

Snails

Small pointed (conical) snail (Prietocella barbara)

Description

The small pointed snail has a conical shell with brown bands of varying width. It is usually less than 10mm in length or diameter.

Habits

Small pointed snails are not restricted to alkaline soils. These snails survive the summer in many habitats - under leaf litter, under the soil surface (up to 50mm), under stumps or stones and climb posts and vegetation. This behaviour of climbing up on vegetation makes it a contamination risk at harvest.

White Italian snail (Theba pisana)

Description

White Italian snails are predominantly white, often with fine brown concentric lines of varying intensity. The body of the snail is creamy-white and the shell is 10-20mm in diameter. The umbilicus (the hole about which the shell spirals) is partly obscured.

Habits

This species thrives in areas of alkaline sandy soils with high calcium content, mainly near the coast. Be aware of snails before liming paddocks as lime aids survival.

It survives during summer off the ground on vegetation and posts, and is commonly found on green weeds. This over summering behaviour of sealing itself on vegetation off the ground makes it a contamination risk of harvested grain.

Vineyard or common white snail (Cernuella virgata)

Description

The vineyard snail resembles the white Italian snail in size and colouring. However, the umbilicus (the hole about which the shell spirals) of the vineyard snail is entire and not partly obscured as with the white Italian snail.

Habits

This species thrives in areas of alkaline sandy soils with a high calcium content, mainly near the coast. It survives during summer off the ground on vegetation and posts. If lime is applied to paddocks where this snail is present, it will aid the survival of the population. Be aware of snails before liming paddocks.

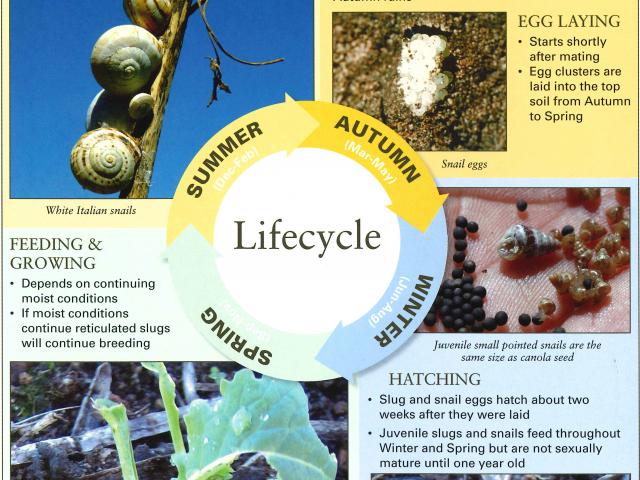

Biology of slugs and snails

Snails and slugs have similar biologies. They are hermaphrodites - both members of a mating couple can lay eggs. Mating usually takes place from mid-autumn to mid-winter when favourable moist conditions return after summer.

Two to four weeks after mating, spherical pearl-white eggs are laid into moist soil. Egg laying can continue from the break of the season to late winter. However, eggs can not survive a hot, dry summer or lie dormant in the soil. After laying, eggs hatch in two to four weeks, but young slugs and snails usually become sexually mature after one year.

Damage

Snails are not known to damage seeds, but may damage germinated seeds close to the soil surface. However, slugs, especially black keeled slugs, will feed in the furrows on seeds of legumes. These slugs are not known to feed on ungerminated canola or cereal seeds.

Irregular pieces chewed from leaves and shredded leaf edges are typical of snail and slug presence. Damage to canola and legume crops can be difficult to detect if seedlings are chewed down to the ground during emergence.

Cereal crops are likely to survive damage by slugs and snails, while canola and lupins can not compensate for the damage or loss of cotyledons. If cereals are deep sown into a fine, firm seedbed, the slugs and snails are not able to feed on the growing point and emerging crops may recover from damage after treatment.

Different species of slugs cause differing amounts of damage. Cereals are less likely to sustain damage from reticulated slugs, than from black keeled slugs. Canola crops need careful monitoring to assess plant losses.

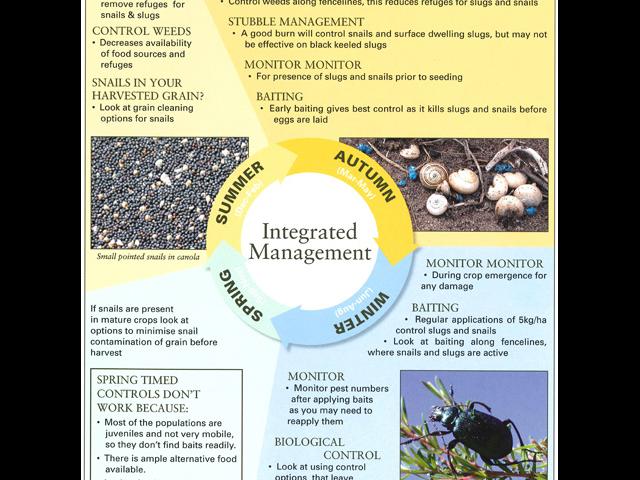

Integrated control – attacking the weak links in the life cycle of slugs and snails

From a management point of view, slugs and snails have similar lifecycles. This means similar management techniques can be employed to control them in broadacre crops. Effective management requires applying controls that coincide with different phases of the pest’s lifecycle.

Control options

Each of the control measures outlined below, if applied only by themselves are unlikely to provide optimum control. An integrated approach needs to be considered to protect crops from damage by slugs and/or snails.

The key to effective control is monitoring:

Monitoring regularly, means pests can be detected early, ideally before seeding as there are more control options available at this time. Once the crop has been seeded and germination is commencing, control options are limited to baiting. At this time crops should be examined at night for slug and snail activity.

It is best to look for slugs and snails on moist, warm and still nights. Fresh trails of white and clear slime (mucus) visible in the morning also indicate the presence of slugs or snails. However, prior to and after applying control measures, it is necessary to estimate how many slugs and snails are present.

It is a good idea to monitor in:

- January/February to assess stubble management options for slug and snail management

- March/April to assess options for burning and/or baiting

- May to August to assess options for baiting especially along fencelines

- For snails 3-4 weeks before harvest to assess risk of snail contamination of grain and if required, implement options to minimise the risk.

How to find slugs

A useful method to detect areas infested with slugs, prior to seeding or crop emergence, is to lay lines of slug pellets with a rabbit baiter. In infested areas, slugs are attracted to the freshly turned soil and pellets placed in the furrow. Very large numbers can be found dead or dying in the furrows or nearby. On sloping ground, furrows should be run along contours to reduce the risk of soil erosion in the event of heavy rain.

An alternative method to gain an indication of the numbers of slugs present in a paddock is to place wet carpet squares, hessian sacks or tiles on the soil surface. They should at least be 32x32cm (10% of a square metre). Place pellets under them. After a few days, count the number of slugs under and around each square. Multiplying by 10 will give an estimate of slugs per square metre (/m2), at least 1-2 slugs/m2 will cause damage to canola. The table below gives an indication of thresholds.

How to find snails

Snails are usually found on stumps, fencelines and under stubbles. A good way to determine snail numbers on open ground is to use a 32x32cm square quadrant and count all of the live snails in it. This is an area of 10% of a square metre so multiplying by 10 will give an estimate of snails/m2.

Consider control options if slug and snail numbers are above thresholds

| Species | Oilseeds | Cereals | Pulses | Pastures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black keeled slug | 1-2/m2 | 1-2/m2 | 1-2/m2 | 5/m2 |

| Reticulated slug | 1-2/m2 | 5/m2 | 1-2/m2 | 5/m2 |

| Small pointed snail | 20/m2 | 40/m2 | 5 per seedling | 100/m2 |

| Vineyard snail | 5/m2 | 20/m2 | 5/m2 | 80/m2 |

| White Italian snail | 5/m2 | 20/m2 | 5/m2 | 80/m2 |

Please note: the above thresholds are from limited data. It is essential to carefully monitor crops as distributions of snails and slugs are patchy.

Pre-seeding management

Burning

Burning prior to seeding, is one of the most effective methods for pre-breeding snail control and provides some slug control. The burning itself kills snails but does not kill slugs. The lack of food and shelter following a burn makes it more likely that slugs will move elsewhere.

Before deciding to burn, soil type and weather conditions need to be taken into consideration. Also, summer weeds should be desiccated and browned off. Rocks also provide hiding places and these, if possible, should be turned by cabling or fire harrowing just prior to burning.

It is important to ensure that an even burn is applied across the paddock, as unburnt patches will provide habitats (refuges) especially for snails. An even burn causes 80-100% kill, patchy burn 50-80% kill. Burning on a warm day with little wind in a paddock that has a reasonable fuel load should achieve good control, can be less effective on small pointed snails if rocks are not turned.

When snail populations are large, a strategic burn every three or four years will assist in controlling snail numbers.

Grazing

Grazing animals will knock snails from stubble and may also trample them. Grazing will also decrease the stubble load into a paddock about to be seeded. Decreasing stubble ground cover will decrease refuges for slugs and snails.

Tillage

The most effective form of tillage to reduce numbers of snails and slugs is wide points or full-cut discs that are used in conventional tillage methods. Ploughing the soil to a depth of 5cm or more will bury surface snails and slugs. Burying snails, especially small pointed snails, can reduce surface numbers of snails by around 40-60%.

Conventional tillage may have limited impact on black keeled slugs. Tillage will disrupt burrows made by these slugs and may cause some mortality. However, it is unlikely that tillage alone will decrease the number of black keeled slugs sufficiently to protect crops.

If tillage coincides with egg laying by slugs and snails, it may expose buried eggs to the environment. This may cause eggs to dry out and die, thereby decreasing slug and snail populations.

Cultivation of the soil does bury surface trash, disturbing potential shelters for slugs and snails. Ploughing trash residues after harvest has been found to remove over-summering habitat for slugs and snails.

Chemical control

Baits

Slugs and snails can only be controlled by baits if they are mobile and looking for food. Note that young snails ie those less than 7mm in diameter for round snails and 7mm in height for conical snails are not likely to be controlled by baits. Young snails feed on decaying plant matter and are not likely to be attracted to baits.

Snail and slug numbers should be monitored to determine if there is a need to bait especially during crop emergence. Baiting will generally only kill 50% of a slug population at any one time and then mainly the larger ones. Younger slugs may emerge in successive waves. Monitoring numbers (refer to Table 1) will determine if there is a need for multiple bait applications. Based on this, baiting can be confined to areas of high snail/slug density.

All baiting must be stopped at least two months prior to harvest to ensure baits are broken down and do not become a contaminant of grain.

When to bait

The best time to apply pellets is early in the season when morning temperatures are low and dew forms, and after the first good germinating rains - this is when slugs and snails begin emerging and are looking for food. Killing mature slugs and snails before autumn egg laying reduces the potential population build up for that season.

Late bait applications are less effective as there is a lot of green material that provides an alternative food source.

Non-rainfast pellets may become covered by soil during rain and decay after wetting. Consider reapplying baits after heavy rain.

Bait rates

Baiting with multiple applications at the lowest registered rate rather than a single application of a high rate is best as the pellets lose their effectiveness after a few nights.

Consider increasing baits up to the highest registered rate if there are more than 80 snails (either round or conical) and 10 or more slugs per m2.

Even bait coverage increases the likelihood of slugs or snails encountering the bait and feeding on the bait. Trials suggest 30 baits per square metre give good control.

There are many bait types on the market. These vary in their spreadability and cost. See 'Snail and slug baiting guidelines' in the link section.

Fence line and border baitings

Snails, especially, aestivate on fence posts and road side vegetation, while slugs may aestivate under road side vegetation. In autumn, when snails and slugs are active, these areas may have a high level of activity. Repeated baitings in these areas can lead to high pest mortality. If snail and slug pressures are high consider baiting at higher rates.

Sprays

There are no sprays registered for snail and slug control in broadacre cropping. Be aware that insecticides commonly used to control insect pests of broadacre crops are not effective against slugs and snails.

Weed control

Summer weed control

The presence of summer weeds may reduce the effectiveness of fire in controlling slugs and snails. Green weed material may protect these pests from fire. A combination of desiccating weeds and using control methods such as burning and baiting can reduce snail numbers by up to 95%.

Summer weeds also provide habitat and food sources for slugs and snails. If there is sufficient moisture, slugs and snails will continue to feed however, only the reticulated slug will breed during summer if these conditions continue.

Fenceline weed control

Slugs and snails reproduce less on bare ground. Maintaining a weed free zone approximately two metres from either side of a fence line may help to remove potential breeding grounds.

Biological control

There are a range of native ground beetles (family Carabidae: carabids) that are generalist predators, which attack slugs. These beetles would normally eat other prey, but some have been found to have a significant impact on slug populations. They can be important factor in controlling slugs, in combination with baiting.

The only biological control developed for snails (by the South Australian Research and Development Institute) is a parasitic fly, Sarcophaga penicillata. Its effectiveness has been limited.

Further research is continuing into finding effective biological control agents for snails.

Minimising harvest contamination by snails

If snail numbers remain above control threshold levels of 20/m2 in cereals and 5/m2 in pulses and canola then it is likely they may be present in harvested grain. This can occur if snail management practices early in the season were not applied or management of the snails was ineffective.

As the harvest season progresses snails migrate up the crop to escape the hot ground. Early in the harvest season snails are more likely to descend to the ground if there is a rain event rather than later in the season. If it is possible, harvest should be timed to coincide with cooler conditions.

Snails have been found to move into windrows (swaths) of crops that were windrowed green (for example, canola) and left to dry. However, windrowing cereals earlier and in cooler conditions may result in lower snail numbers.

Round snails (white Italian and vineyard snails) are more likely to be dislodged off crops during harvest. However, small pointed snails are often found in sheltered locations such as between the leaf and stem and are difficult to dislodge. These snails are more likely to be intact in the harvested grain.

Harvester modifications are more effective on round rather than conical snails. Cleaning grain after harvest may remove small pointed snails from the grain. For more information refer to Bash'em, Burn'em, Bait'em: Integrated snail management in crops and pastures, published by the South Australian Research and Development Institute.

Acknowledgements

Authored by Svetlana Micic, Entomologist, Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (DPIRD); Ken Henry, South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI); Paul Horne, Entomologist, IPM Technologies, Victoria.

This work was produced with funding from the Grains Research and Development Corporation.

The following are gratefully acknowledged for their contributions:

Judy Bellati, SARDI; Peter Davis, DPIRD; Tony Dore, DPIRD; Dennis Hopkins, (retired) SARDI; Nathan Luke, SARDI; Stewart Learmonth, DPIRD; Peter Mangano, DPIRD; Phil Michael, (retired) DPIRD; Michael Nash; Marc Widmer, DPIRD.